The Church's Confession of Faith

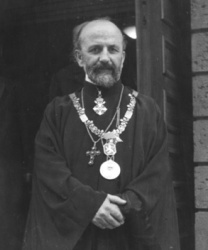

PROFESSOR DR. STEFAN ZANKOV

University of Sofia, Bulgaria (Orthodox)

[190]

I

For us of the Orthodox Church it is a self-evident axiom that where the one Church, or Christian unity, is found, there also is found the one Christian truth, and consequently one Christian faith, and hence one Christian Confession of Faith.

The well-known passage in which the Apostle speaks of

[191]

“one faith " (Eph. 4:6) cannot be construed, whether from a natural or historical point of view, in any other sense than as a "doctrine," a creed.

A faith and a doctrine (or a creed) can only fail to correspond with one another in the sense that the substance and the idea may fail to correspond with the form and words in which they are expressed or rendered. Nevertheless, bearing in mind the dualism of human nature, we have no right to treat the idea and the words (or the faith and the doctrine) as opposite conceptions. Corresponding to every idea, there is a word; corresponding to every faith there is a doctrine, or a creed.

Moreover, it follows from the very nature of the subject that when the Apostle spoke of one faith, he was also speaking of the one religious truth which is apprehended by that faith, and at the same time of one doctrine (or confession of faith) which is the expression of that truth.

Moreover, the whole tenor of the Holy Scriptures, indeed the very Scriptures themselves, and the whole history of the Christian Church from the time of the Apostles and their disciples convince us that, in the first place, there was always one faith, held and required, in the one Church of Christ; and secondly, that the true faith was never and could never have been distinguished from the one religious truth and from the one religious doctrine (or confession of faith).

For even from an entirely empirical standpoint there never was, nor is there, nor can there ever be, any religious body, far less a Church, not possessing a fundamental faith and a doctrine (or confession of faith) as the expression of that faith. Christianity without its principle would be something utterly inconceivable, and a Christian Church without a principle would be even more inconceivable and absurd.

It is, indeed, the extraordinary importance, nay more, the indispensability of a correct confession of faith as an expression of the true Christian doctrine, which accounts first for the diversity and multiplicity of the creeds in use in the different Churches, and secondly for the steadfast

[192]

attachment of every Christian Church to its own confession of faith.

To have one Church, and at the same time to allow the widest possible diversity of faith and creed within its bounds, would mean either that the essential nature of the Church as a unity was not understood, or that the Church in question was not in reality the Church of Christ; or else indeed that there was indifference towards the Church and towards ecclesiastical unity.

The chief argument which is used against the necessity of having a single faith or creed in a single or unified Church is that all faith is a matter of personal conviction, and that personal conviction can only be possible where there is personal freedom. We of the Orthodox Church consider that though these words may be correct in themselves, their use in this connection rests on a misconception, and that the argument is not relevant to the real point at issue. Undoubtedly, every person is free, according to his conviction, to believe in and acknowledge Christ or not to do so. But if he does not believe in Christ, he is not a Christian, and has no interest in the Christian Church whereas, if he believes in Christ he must also confess Christ. And so long as he holds this belief it is illogical to speak of a freedom which would make it lawful for him to be a Christian, and yet not to believe in Christ! And this applies with the same force to the acceptance of all other fundamental truths of the Christian religion and the Christian Church. It is therefore idle, in discussing this problem, to seek to establish an antithesis, and to represent truth and faith (hence, doctrine and creed) as standing in opposition to freedom and conviction. The religious truth is objective (God, Christ, and so on); that is to say it exists, and will continue to exist, even independently of our personal conviction and freedom of judgment. Faith is the inward, personal, spiritual path through which the religious truth is apprehended, experienced and discerned, and it is also the inward vessel in which this truth is contained. The creed is the external expression, formulated in words, of this truth and this faith. These three elements are thus

[193]

one in source and origin. They are in no way antithetical to freedom and conviction, which rather form a background for them.

For the same reasons we regard it as an error to suppose that the creed, because it is an external form, fetters or might fetter the living faith. If this view were to be generally applied, the Bible and the Church must themselves be regarded as external forms, so that the whole movement for the unity of the Church would be stultified.

Nor can we attach any value to the objection that the creed is related to and conditioned by historical events. All things are related to history: the Incarnation, the Bible, etc. But this relation does not imply any relativity in religious facts or truths, although their accomplishment and revelation have their place in history and have found verbal expression in the creeds.

Accordingly, we of the Orthodox Church hold steadfastly to the belief that where the Church is found, there must also ipso facto be found Faith, Doctrine, and Creeds and that where the one Church of Christ is found, there are found, or ought to be found, one Faith, one Doctrine and one Creed.

II

What then is the confession of faith of a united Christendom? Or what could or should such a confession consist of? Should it be a new confession of faith, or one of the ancient symbols?

The extraordinary difficulty of drawing up a new form of creed or securing its acceptance is plain to everybody, more particularly in the present situation of Christendom. Any new creed drawn up for a united Christendom would need to be so formulated as to express in its articles the essentials of Christian truth in a manner that would be acceptable to the individual Churches—since the object aimed at would be to have a single creed, which would form a single bond of faith. But at the first attempt to determine the articles of such a creed, every one of the issues which now keep Christendom disunited would immediately

[194]

arise. In short, it is evident that any new "midway" creed, which aimed at reconciling the extreme right and the extreme left, would be a futile undertaking, because, in matters of religion, no reconciliation is possible between truth and error, between affirmation and negation; and any such creed would, in effect, be a more or less unsubstantial and consequently valueless collection of phrases. The same argument applies to any attempt to formulate a new creed containing a minimum of Christian truth. For there can be no minimum or maximum in Christian truth.

And again What generally accepted standard could we find for the numerous Christian Churches of today, when we come to draw up the articles of the new creed? And what guarantee could we have that this standard would be a correct one? And what would be the prospects of securing universal acceptance either for that standard or for the new creed which would be founded upon it? When we begin to fathom the difficulties of drawing up a new confession of faith, we are compelled, in spite of ourselves, to admit that there is grave danger lest these very difficulties might wreck our endeavours to re-unite Christendom, and lest, after all our efforts to compile such a creed, the Churches should. be more widely separated than before the attempt was made.

We find that the situation is exactly reversed if we take the Nicene Creed as the Symbol of Christian unity.

First as regards the inward truth of the Creed. From our Orthodox standpoint, the only guarantees of truth are first the Church itself, and secondly and allied to the first, the catholic character of the truth, as being the truth of the Church. Outside the boundaries of the Ecumenical Church and of Catholicism, there is nothing which is not open to challenge. But the converse is not true—unless we are advocates of ecclesiastical nihilism or of some Christian atomic theory! The Church is the "fulness" and the "pillar and ground of truth," and the truths of the Christian religion can only be apprehended in all their aspects if they are given to us as "catholic" truths, that is to say, if all the Christian Churches, going back to the times of the

[195]

former undivided Church, have endorsed them. Now that is the case in regard to the Nicene Creed. If it were otherwise, that Creed would be a document possessing only an historical or archeological interest for us. But, as it is, the Nicene Creed is the confession of faith of the whole undivided ancient Church, and we cannot perceive any reason why this Creed should not, or might not, become the Creed of a later united Christendom.

The acceptance of the Nicene Creed as the confession of faith of the united Church would be all the more intelligible and natural because it is already the Creed of two-thirds of Christendom and is held in great honour in the remaining third.

Moreover, the Nicene Creed has two advantages: first, that it is short, being a statement of the primary essentials of the Christian faith; and secondly, that its acceptance would exclude all questions of equality or inferiority, such as might arise in the selection of a single confession of faith for a united Christendom.

Surely it must be admitted that, if Christendom of today is not ripe to accept the Nicene Creed as a common confession of faith, then this same Christendom is far less ripe for the attempt to draw up, and secure acceptance for, a new common creed.

For these reasons, we of the Orthodox Church hold that the only possible and the only necessary confession of faith for a united Christendom, today, is the Nicene Creed—that is to say, the Symbol of the ancient united Christian Church—and that the acceptance of this creed must precede any attempt to draw up a new common confession of faith.

III

At the same time, we must say frankly that in our view the acceptance of this Creed would only be of real significance if its validity, in the fullest sense of that word, were generally admitted.

IV

We do not think that the occasions on which this Creed would be used in Church services or the manner of its use

[196]

are issues of primary importance, at any rate at the beginning.

And now, beloved Fathers and Brethren, we will conclude our observations with an appeal borrowed from the liturgy of our Orthodox Church: "Let us love one another, so that we may confess God in unity of Spirit."